來讀讀Leveson對於Hollnagel的批判(兩位國際安全韌性大神筆仗)

Safety III: A Systems Approach to Safety and Resilience

https://psas.scripts.mit.edu/home/nancys-white-papers/

與其論斷孰高孰低或孰是孰非是(我算哪根蔥)

讓人慶幸的是:自己可以賞味理解兩位大師的觀點差異

- Leveson是航太工程背景,她所陳述的Safety III或許可謂是航太軍工產業的嚴謹理想,強調在統計量化的基礎上建力模型與進行simulation,相對適用在PSM、產品安全

- Hollnagel乃至於Reason是社會心理背景,陳述的”系統模型(心智模式)”或Safety II,是一般組織與高階主管看待安全與意外的認知與盲點,可謂是質性研究,相對適用在職場安全管理

- 業界的安全水準與認知可謂多半停留在Safety I(“相信”所有事故都可以預防、人為疏失佔98%、行為安全與指差呼喚、Heinrich….);想起吳聰智老師臉書的分享:如果你走得太超前,你的士兵可能會把你誤認為敵人- W. Welsby

Does Safety-I Exist?

Erik Hollnagel提出的“Safety-I”概念,但對Safety-I的描述具有誤導性=>與各行業中實際安全工程實踐的現實不符。這是稻草人謬誤,他曲解工程師對於安全的信念和實務(認定工程師相信他們可以預見並防止所有事故,或者認為人類只是系統組件),以使自己的立場看起來更合理。

多少同業喊”所有的事故都是可以預防的”+”預防人為疏失(把人事為可靠度不佳的零組件)”=>不能完全否定Hollnagel提出的“Safety-I”

安全並不是一個跨行業的單一方法,每個行業甚至在同一行業中的個別公司在減少損失方面可能採取不同的方法。安全方法的選擇取決於諸如行業差異、文化變化和歷史背景等因素。工作場所安全和產品/系統安全兩者之間沒有關聯,需要採取不同的方法。

對安全實踐需要進行更加細緻的理解,研究在各種情境下用於預防事故和提高安全性的方法的光譜。對各種情境中有效的安全方法進行全面分析對於有效推進安全實踐至關重要。

指差呼喚(pointing and calling)看似白癡+把人貶低為工具,但對於預防恍神與防呆就是有用有效

重大事故發生後的事故調查,往往只是獵巫與治標不治本=>修理懲罰出錯的人,那個導致事故一再發生的組織與該負責的高層有權無責,e.g.,台鐵、消防

Differences between Workplace Safety and Product/System Safety

作為一名社會科學家,Hollnagel在安全工程領域的經驗有限,參考文獻主要聚焦於社會科學,忽略了安全工程方面的文獻。未能區分工作場所安全和產品/系統安全的方法。產品/系統安全的實踐與工作場所安全不同,並且在不同行業之間存在差異。

工作場所安全,也被稱為職業健康與安全、工業安全或工業衛生,主要集中於預防工人在工作職責期間受傷。它通常強調行為心理學,以鼓勵工人遵守規則和程序。相比之下,產品/系統安全則專注於所設計和使用的產品/系統的危險,較少關注工人行為,更注重系統設計。

Hollnagel對工作場所安全主題的討論,如Heinrich's Triangle、Taylorism和行為主義,這些被認為與產品/系統安全無關。它強調了在過去100年中,工作場所安全和產品/系統安全之間在實踐和從業者之間的歷史上缺乏重疊,儘管在工人因工作場所中使用的工程產品而受傷時可能存在聯繫。

Workplace and Product/System Safety History

工安簡史

工業革命早期工人所面臨的挑戰在於工廠中的工人受到不公平對待,普遍態度是他們應該接受工作中涉及的風險。在沒有工人補償法的情況下,受傷的員工必須根據普通法提起訴訟,雇主通常不承擔責任,如果員工對事故有所貢獻,另一名員工參與其中,或者員工在受傷前知道並接受了工作條件中的風險。

工廠中的條件危險,危險設備和不安全條件導致工人經常受傷和死亡。對事故的調查通常歸咎於工人,雇主很少承擔責任。這導致社會的反叛和爭取更好工作條件的抗爭,進而形成了自願安全組織並建立了安全標準。

在歐洲,對工人安全的關注早於美國,德國等國在1880年代引入了工人補償和社會保險。安全立法,如1844年英國的《工廠和車間法》,旨在保護工人免受涉及機械的事故。紡織業等行業面臨確保工人安全的挑戰,導致實施保護性立法。

在美國,雇主對工人安全的漠不關心最終導致社會改革和政府干預以保護員工。1852年通過的調節蒸汽船鍋爐法和1908年紐約通過的第一部工人補償法等法律的通過,標誌著確保工作場所安全的重要一步。

意識到事故會造成金錢損失和生產力下降,加上需要預防傷害的需求,導致公司成立工業安全部門並在重工業如鋼鐵業制定安全標準。這種法律敘述在塑造安全技術發展歷史上發揮了至關重要的作用。

Without workers’ compensation laws, employees had to sue and collect damages for injuries under common law. In the United States, the employer almost could not lose because common law precedents established that an employer did not have to pay injured employees if:

1. The employee contributed at all to the cause of the accident: Contributory negligence held that if the employee was responsible or even partly responsible for an accident, the employer was not liable,

2. Another employee contributed to the accident: The fellow-servant doctrine held that an employer was not responsible if an employee’s injury resulted from the negligence of a co-worker, and

3. The employee knew of the hazards involved in the accident before the injury and still agreed to work in the conditions for pay: The assumption-of-risk doctrine held that an injured employee presumably knew of and accepted the risks associated with the job before accepting the position

技術觀點的工安發展史

討論了安全工程的歷史演變,強調了從專注於職場安全轉向將安全納入產品設計的過渡。最初,工程師們在工業時代開始認識到安全設計的必要性,當時設計的機器存在危險,導致人員死亡。早期的安全措施包括戴維安全燈和喬治•韋斯汀豪斯基於鐵路上開發的壓縮空氣制動器,突顯了將安全與功能性並重考慮在設計中的轉變[Roberts, 1984]。

隨著工程設備在工作場所中的使用增加,安全工程和職場安全密切相關。像是工廠事故預防協會這樣的組織在研究事故和促進安全改進方面發揮了關鍵作用。到了19世紀末,工程師開始認識到從一開始將安全納入設計的重要性,而不僅僅是事後添加護罩[Roberts, 1984]。

職場安全和產品/系統安全之間的分歧大約發生在1930年代左右。1929年海因里希對工業事故進行的研究突顯了不安全行為和條件的普遍性,引發了對事故中人為因素的關注。這一轉變引發了有關工人與不安全機械在事故中角色的爭論,有些人將許多事故歸因於人為錯誤[Heinrich, 1931]。

儘管強調人為錯誤,但早期就認識到將安全設計到機械和設備中以減輕人為缺陷的重要性。這種對安全設計的積極態度旨在使個人在進行任務之前必須進行安全關鍵操作,這反映了工業機械設計中的基本原則[Hansen, 1915]。

將安全原則納入工程實踐的整合是一個持續的過程,旨在預防事故並提高各行業的整體安全標準。

工程師觀點的職場安全

安全實踐隨著時間演變,工作場所安全責任從逐漸從員工轉移到雇主,強調雇主提供安全工作環境和必要工具的重要性,而不僅僅依賴個人工人的責任。

政府介入也影響享了工作場所安全,例如十九世紀立法要求鐵路設置自動連接器,從而顯著減少了工人的死亡和傷害。

工作場所安全和產品/系統安全,兩著約在70年前產生分歧:兩個領域之間的教育計劃、認證要求、監管機構、法規、管理結構和實踐之間的明顯差異。工作場所安全和產品/系統安全之間的缺乏重疊。

例如德州城煉油廠爆炸和深水地平線井噴就是例子。多數情況行業,這兩個領域的培訓、實踐和管理有很大不同,並且存在認識到一個領域的專家不是另一個領域的專家,並且將他們混合在一起可能會導致兩者都不是專家做得很好。根據我的經驗,公司內的兩個團隊通常很少或根本沒有交互作用也沒有任何共同點

難怪PSM和ISO-45001兩者格格不入,彼此雞同鴨講,因為底層邏輯不同

將行為主義與工作場所安全聯繫在一起,討論了工作場所中的行為是如何受到通過強化和懲罰進行的條件化影響。它澄清了雖然工作場所安全強調遵守指定程序,但程序和遵守在安全工程中的作用因行業而異。

哈,Leveson一樣對行為ABC理論很感冒

Safety-I概念更接近與適用於職場安全,而不是安全工程(PSM),這可以從他書中對海因里希、海因里希金字塔和其他職場安全話題的強調中看出,幾乎沒有提到產品/系統安全的例子或大多數的實踐。所以讓我們來看看過去70年來產品/系統安全的實踐。

工程師角度的系統/產品安全

專注於消除、預防和應對危害,而不是專注於人類的行為或行動,甚至不是事故本身。危害通常是系統的狀態,可能導致損失,而不是損失本身。損失通常被標記為事故、失誤或事件。

為什麼引入危害的概念?事故可能涉及工程師或系統設計師無法控制的條件。考慮一個化工廠。當化學品意外釋放出來時,氣象條件使得化學品轉移到人類所在的地方(而不是無害地散佈到大氣中),並且在這個時候有人類或其他相關實體在化學品的路徑上。化工廠的設計師唯一能控制的部分是化學品的意外釋放。這並不涉及損失本身,但是是一種在最壞情況下可能導致損失的狀態。這種狀態被稱為危害。汽車的例子是違反前方車輛的最小距離或轉換到另一條車道有另一輛車。在第一種情況下,制動距離可能取決於能見度和路況。在第二種情況下,另一條車道上的另一名司機可能能夠避開你,但你無法真正控制他們的行為和他們車輛的狀態。因此,重點是預防危害,這是我們可能可以控制的。

產品/系統安全涵蓋了各種各樣的實踐。試圖將其簡化為一種簡單的刻板方法是誤導的:我們努力減少損失的方法並不是單一的。安全的方法因行業而異,有時甚至在行業中的每家公司也不同。不同國家之間存在一些差異,但在很大程度上,這些地理差異被行業之間的差異所淹沒。這些差異通常是由於這些行業中危害的不同性質所引起的,但也是由於行業中不同的歷史和傳統以及它們的整體安全文化所引起的。

安全工程基於與工程的其他方面相同的科學和數學基礎。用於改善安全性的程序是工程中使用的程序,主要是建模和分析,在這種情況下應用於危險系統狀態。目標是識別危害,然後設計、製造、運營和管理系統,以消除或減輕已識別的危害以防止損失。此外,在工程領域,術語“安全”通常被廣泛定義為不僅包括人員受傷(如工作場所安全)而且包括對物理設備的損壞—例如飛機或太空船—甚至在人類健康或甚至設備損失可能不是一個問題但任務至關重要的情況下的任務損失。

不同行業共通的活動

大多數安全工程努力中都有一些共同的活動,儘管在不同行業中進行這些活動的方式可能有所不同。這些活動包括:

危害分析:危害分析用於在系統設計和開發過程中識別危險狀態,並確定系統如何進入危險狀態。已經開發了許多不同的技術來進行危害分析,但所有這些技術都是從利益相關者識別的危害出發,利用有關技術的基本科學知識以及對該行業事故發生的了解或假設,生成可能導致危險狀態的系統組件的情景或行為。

安全設計:這裡的目標是利用從危害分析中獲得的信息,在事故發生之前工程或“設計掉”事故,也就是預防危害。一般來說,這是通過各種行業獨有的設計流程和這些行業的危害特徵來實現的。最高優先級是創建不能進入危險狀態的設計。如果這個目標不可行或不切實際,那麼(按優先順序)將設計以防止危險狀態的發生,減少其發生,或者在發生時做出反應並將系統移回到安全或更安全的狀態,以防止或減少損失。

主要目標是從原始設計中消除危害。危害可以通過消除系統操作中的危險狀態(創建固有安全設計)或消除與該狀態相關聯的負面後果(損失)來消除 - 如果一個狀態不能導致任何潛在損失,那就不是危害。當然,從哲學上講,幾乎沒有什麼是不可能的。從實際的工程角度來看,一些物理條件或事件的發生是如此遙遠,以至於考慮它們是不合理的。危害消除可能涉及用一種無危害或較少危害的材料替換另一種材料。例如,用不易燃材料替換易燃材料,或用無毒物質替換有毒物質。

總是存在著權衡取捨。有些危害根本無法消除,而不會同時導致一個無法實現其目標的系統。在太空船設計中冒更多風險可能比在商用客機中更有道理。所有損失並不具有相同的優先級。如果無法消除危害,則將嘗試減少其發生。例如,如果在危害分析中確定了組件故障是一個原因,則可以使用互鎖裝置,提高可靠性,建立安全裕度等。例如,壓力釋放閥設計帶有互鎖裝置,以防止所有閥門同時關閉,禁用汽車點火裝置,除非自動變速器處於“停車”狀態,汽車引擎冷卻系統中的凍結塞將會被擠出而不是裂開汽缸,如果水在缸體中凍結,則熔化。同樣,為了防止過熱,鍋爐中的熔化塞在水位降至預定水平以下時暴露,因此熱量不會從塞子上移開,然後熔化。開口允許蒸汽逃逸,降低鍋爐中的壓力,並消除爆炸的可能性。

安全裕度涉及設計一個組件以承受比預期發生的更大應力。冗餘性可用於引入重複以提高可靠性,儘管這種方法存在許多缺點和限制,例如冗餘組件的共同模式和共同原因故障。此外,冗餘對於軟件組件或組件設計錯誤並不有用。

由於通常無法確保設計防止所有危害的發生,因此通常還會嘗試設計以在損害發生之前控制危害,即使盡管努力消除或減少它們,它們仍然發生。例如,即使使用了安全閥來保持壓力低於特定水平,鍋爐可能存在缺陷,使其在低於安全閥設定值的壓力下爆裂。為了應對這種情況,建築代碼可能會限制在人口密集地區中可以使用的蒸汽鍋爐壓力。系統中設計的保護措施,以應對危害發生時防止或限制損害,可能包括設計以限制危害的暴露,隔離和封裝,保護系統和失效安全設計。

Finally, the last resort is to design to reduce potential damage in the case of an accident, such as alarms and warning systems, contingency planning, providing escape routes (e.g., lifeboats, fire escapes, and community evacuation), or designs that limit damage (e.g., blowout panels, collapsible steering columns on cars, or shear pins on motor-driven equipment).

Human factors engineering and human-centered design: In human factors engineering, psychological concepts are applied to engineering designs to prevent human errors and provide human operators with the ability to safely control the system. More focused human-centered design concepts started to be developed in the 1980s and were first applied in the aviation community. In this approach to engineering design, the role of humans in the control of systems is the focus from the beginning of engineered system concept development.

Operations: Systems must not only be designed to be safe, but they must also be operated safely. Operational safety involves considerations for operability in the original design and for managing operations to ensure proper training of operators, identifying and handling leading and lagging indicators of risk, management of change procedures, maintenance procedures, etc. Data collection and analysis during operations has played an important role in improving design and operational safety.

Management and Policy: Emphasis on the design of Safety Management Systems is a relatively recent emphasis in system safety engineering, dating back to the middle of the last century.

Accident investigation and analysis: Every industry investigates accidents, but it is usually a small part of the safety engineering effort.

Regulation and Licensing: Regulation may involve rules enforced by an oversight agency, voluntary standards, or certification/licensing of new systems. Regulation usually involves some type of approval of new systems before they are allowed to be used. It also almost always includes oversight into the operation of the systems to ensure that assumptions about operation (such as maintenance assumptions) made during analysis, design, and certification of the system hold in the operational environment and that changes over time are not leading to increasing levels of risk. If such dangerous conditions are caught in time, accidents can be prevented. Examples of ways that oversight agencies collect information during operations include licensee event reports in nuclear power plants, aviation safety reporting systems, and auditing of airline and airport operations.

產品/系統安全領域的主要重點是通過產品開發期間的設計和分析活動以及在運營期間的控制和反饋來工程化系統以預防事故。幾乎每個行業和公司都會調查事故,不這樣做是不負責任的:獲得的信息對於改進預防活動和我們的基本工程知識至關重要。然而,據我所知,沒有任何一個行業僅依賴調查,甚至將其置於積極預防之上。

終於知道講管理系統的談消除取代工程控制有多麼怪異:消除犯錯的人、取代常常犯錯的人、(薪資)工程控制不聽話的人

嘗試整合製程安全與職場安全的人,通常暨不懂製程安全也不懂職場安全,只懂最基本控制危害與風險,可惜絕大多數公司高層、官方官員乃至於顧問就是這樣的水準

化工業的安全實務

化工(製程)行業的工藝和材料本質上具有危險性,安全方法是由保險需求推動的。因此,該行業通常使用的術語“損失預防”反映了這些起源。

在化工和石化行業,三個主要危害是火災、爆炸和有毒物質釋放。在這三種危害中,火災最常見,爆炸較少見但造成的損失更大,有毒物質釋放相對較少,但卻是造成最大損失的原因。由於洩漏是所有這些危害的先兆,損失預防的重點很大程度上類似於核工業(通常被認為是過程工業的一部分),即避免爆炸或有毒物質通過洩漏、破裂、爆炸等途徑洩漏。

與化工行業相關的三個主要危害在幾十年來基本上保持不變。消除或控制這些危害的設計和操作程式已經發展並納入了化工行業協會和其他組織制定的法規和標準中。這種方法在二戰前足夠了,因為該行業規模相對較小,發展速度足夠慢以通過經驗學習。然而,二戰後,化工和石化行業開始以驚人的速度增長複雜性、規模和新技術。重大危害的潛在性也相應增長。化工廠的運營也變得更加困難,啟動和停機尤其變得複雜和危險。

過去,製程工業中的安全努力主要是自願的,基於自身利益和經濟考慮。然而,污染已經成為公眾和政府越來越關注的問題。重大事故引起了巨大的宣傳,並產生了政治壓力,要求立法以防止未來發生類似事故。大多數這些立法要求進行定性危險分析,包括識別最嚴重的危險及其影響因素,並對最重大事故潛在性進行建模。

在化工行業應用危險分析與其他行業相比存在特殊的複雜性,這使得因果序列的建模特別困難。儘管該行業使用了一些標準的可靠性和危險分析技術,但該行業的獨特特點導致了行業特定技術的發展。例如,許多化學品的危險特性已被充分瞭解,並被編入索引中,用於工廠的設計和運營。

一種為化工和石化行業開發並主要使用的危險分析技術稱為危險與可操作性分析(HAZOP)。這種技術是一種系統性方法,用於檢查工廠中的每個專案,以確定與正常工廠運行條件偏離的原因和後果。通過這項研究獲得的有關危險的資訊被用於對設計、運營和維護程式進行更改。HAZOP始於1960年代中期。更新的危險分析技術(如STPA)可以在設計完成之前進行,並利用結果建造更簡單、更便宜、更安全的工廠,避免使用危險材料,減少使用量,或者在較低溫度或壓力下使用它們。當發生損失時,當然會進行事故調查,但更加強調積極的分析和設計工作。

To understand the unique aspects of the System Safety approach and differentiate it from the other approaches to safety developed in parallel but independently for such industries as civil aviation and nuclear power, a few basic concepts can be identified:

• System Safety emphasizes building in safety, not adding it on to a completed design or trying to assure it after the design is complete.

From 70 to 90% of the design decisions that affect safety will be made in the concept development project phase . The degree to which it is economically feasible to eliminate a hazard rather than to control it depends on the stage in system development at which the hazard is identified and considered. Early integration of safety considerations into the system development process allows maximum safety with minimal negative impacts. The alternative is to design the system or product, identify the hazards, and then add on protective equipment to control the hazards when they occur—which usually is more expensive and less effective. Waiting until operations and then expecting human operators to deal with hazards—perhaps by assuming they can be flexible and adaptable, as in Safety-II—is the most dangerous approach.

• System safety deals with systems as a whole rather than with subsystems or components. Safety is a system property, not a component property.

• System safety takes a larger view of hazards than just failures. Serious accidents can occur while system components are all functioning exactly as specified—that is, without failure. In addition, the engineering approaches to preventing failures (increasing reliability) and preventing hazards (increasing safety) are different and sometimes conflict.

• System safety emphasizes analysis rather than past experience and standards.

Standards and codes of practice incorporate experience and knowledge about how to reduce hazards, usually accumulated over long periods of time and resulting from previous mistakes. While such standards and learning from experience are essential in all aspects of engineering, including safety, the pace of change today does not allow for such experience to accumulate and for proven designs to be used. System safety analysis attempts to anticipate and prevent accidents and near-misses before they occur.

• System safety emphasizes qualitative rather than quantitative approaches. System safety places major emphasis on identifying hazards as early as possible in the design stage and then designing to eliminate or control those hazards. In these early stages, quantitative information usually does not exist. And our technology and innovations are proceeding so fast that historical information may not exist nor be useful. The accuracy of quantitative analyses is also questionable. The majority of factors in accidents cannot be evaluated in numerical terms, and those that can will often receive undue weighting in decisions based on absolute measures.

In addition, quantitative evaluations usually are based on unrealistic assumptions that are often unstated, such as that accidents are caused by failures, failures are random, testing is perfect, failures and errors are statistically independent, and the system is designed, constructed, operated, maintained, and managed according to good engineering standards. Some components of high technology systems may be new or may not have been produced and used in sufficient quantity to provide an accurate probabilistic history of failure. Surprisingly few scientific experiments (given the length of the time they have been used) have been performed to determine the accuracy of probabilistic risk assessment, but the results of the few that have been done have not been encouraging.

• System safety recognizes the importance of tradeoffs and conflicts in system design. Nothing is absolutely safe, and safety is not the only or usually even the primary goal in building systems. Most of the time, safety acts as a constraint on how the system goals (mission) may be achieved and on the possible system designs. Safety may conflict with other goals such as operational effectiveness, performance, ease of use, time, and cost. System safety techniques focus on providing information for decision making about risk management tradeoffs.

• System safety is more than just system engineering. System safety concerns extend beyond the traditional boundaries of engineering to include such things as political and social processes, the interests and attitudes of management, attitudes and motivations of designs and operators, human factors and cognitive psychology, the effects of the legal system on accident investigations and free exchange of information, certification and licensing of critical employees and systems, and public sentiment

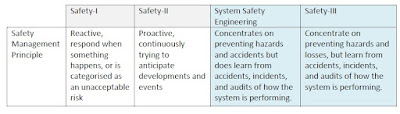

A Comparison of Safety-I, Safety-II and Safety- III

- 對員工或主管而言對的事情,在工安主管眼中是錯的e.g., 用偷工減料的方式,沒出事(好歹沒鬧上檯面)完成工作

- 對員工或主管而言錯的事情,在工安主管眼中是對的 e.g., 不戴防護具作的同仁,發生了被化學品噴濺的工作傷害(合情合理)

- 每個失校故障都是獨立事件(沒有系統性因素或CCF)

- 組織因素(績效、時間、成本等壓力因素,主管霸凌與管理暴政)通常是最大的CCF

- 每個失效故障常有蝴蝶與骨牌效應+牽一髮動全身(很多高階主管很無恥與無知:看不見、當成不知道+視而不見)

- 過度簡化模型+只看橫斷面的機率,讓人對於可靠度與安全性有錯誤的假設

- 簡單線性的因果關係描述,讓人難以看見複雜的交互作用

- The humans in the system, including operators, managers, government overseers, etc. must be aware that a hazardous state has occurred. The hazardous state must be observable within the time period necessary to prevent a loss. The same is true for software or any type of automated system controller that we expect to respond to hazards. Without knowing that a hazard exists, then it is not possible to control it or to respond to minimize damage.

- Accurate information about the current state of the system must be available in a timely manner. The operator must have the information necessary to solve problems.

- The system design must allow the flexibility required to be resilient. If there are no actions that the controller (human operator or manager, software, social structure) has available to recover from a hazard, then the human can be resilient—in terms of knowing what to do—but not be able to respond in any effective way. A simple example is the “undo” button in many software applications. More specifically, if a hazard does occur, perhaps because of errors on the part of the operators themselves, either they must have a means to reverse the errors or move to a non-hazardous state. Or other parts of the system must have this capability.

沒有留言:

張貼留言